Transmitted by sandflies, leishmaniasis affects humans and dogs, with climate conditions like temperature and rainfall significantly influencing its spread.

A recent study led by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center-Centro Nacional de Supercomputación (BSC-CNS) researcher Bruno Carvalho has revealed that climate plays a significant role in the spread of leishmaniasis, a neglected infectious disease transmitted by sandfly bites. Leishmaniasis, which can affect both humans and animals, such as domestic dogs, has been found to be highly sensitive to climatic conditions, with temperature and rainfall being essential factors influencing the activity of sand flies and the development of the parasite they might carry.

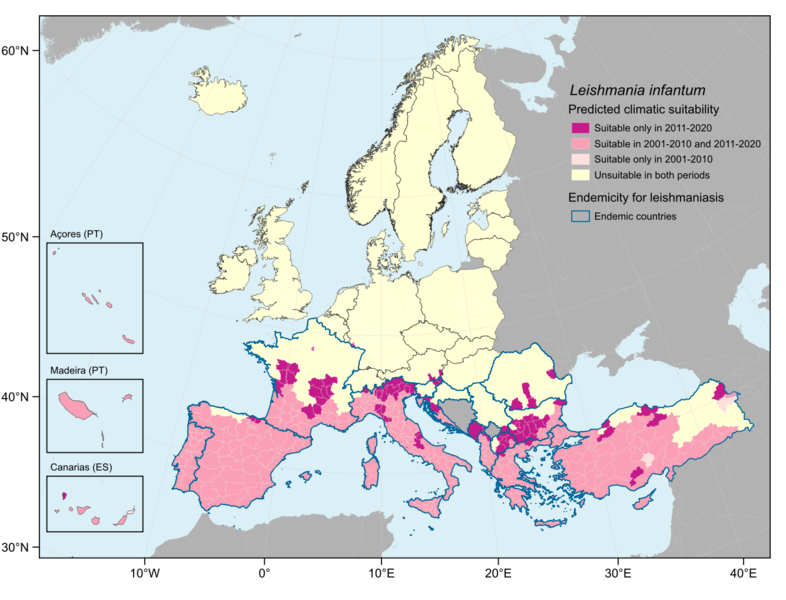

In the study, published in The Lancet Regional Health Europe, Carvalho and an interdisciplinary team of researchers developed an innovative indicator model based on artificial intelligence (AI) to track areas in Europe with favourable climatic conditions for leishmaniasis transmission. This indicator was part of the recently published European Lancet Countdown on Climate Change and Health. Over the past two decades, due to global warming, these areas have increased, especially in southern and eastern Europe, with a noticeable northward expansion toward central Europe.

This modelling study used a machine learning (ML) algorithm―an AI technique that allows computers to learn and make predictions from data―trained with epidemiological, climatic, and environmental data from multiple databases. This ML algorithm then generated predictions about regions with suitable climates for leishmaniasis transmission. The authors then validated these predictions by comparing them with human and canine disease records from France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. The results confirmed a positive relationship between the ML indicator predictions and observed disease incidence, suggesting that areas with higher climatic suitability for leishmaniasis may indeed face a higher risk of human and canine infections.

In southern European countries, leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease, i.e. transmitted from animals to humans. Caused by the species Leishmania infantum, its main domestic reservoir is the dog. But leishmaniasis is not new to Europe. The Mediterranean region has long been an endemic area for the disease, which manifests in different forms, from cutaneous leishmaniasis causing skin ulcers to visceral leishmaniasis, which affects internal organs and can be fatal if untreated. The spread of the disease to new areas is particularly concerning for public health officials, who must consider how to address this emerging threat in regions previously unaffected.

“By mapping regions with favourable climate conditions for leishmaniasis, the study's indicator provides a valuable tool for identifying transmission hotspots. This information can enhance surveillance and support public health decision-making,” explained Bruno Carvalho, the study's first author and a researcher of the Global Health Resilience group at the BSC’s Earth Sciences Department. He added: “With more precise data, health authorities can better allocate resources, implement targeted interventions, and raise public awareness in high-risk areas.”

Along with climate change, another aggravating factor for leishmaniasis transmission is the increasing mobility of people and domestic animals―especially dogs― either due to travel or forced migration. One of the most significant risks is the movement of millions of tourists from the north to the Mediterranean coast. This movement affects not only people but also pets: many infected dogs live in non-endemic areas. As the climate becomes progressively better for sand flies in these areas, infected dogs may become the source of the parasite to establish a local focus of transmission.

Studies have shown that another agent could complicate the epidemiological situation of human and canine leishmaniasis: leishmaniasis in rats. Considering that sewer rats (Rattus norvegicus) are the most widespread mammal in the world after humans and the most abundant animal in cities, the protozoan Leishmania infantum was found in 33.3% of the rats analysed in Barcelona (Spain), for example.

ICREA Professor and leader of the GHR group at BSC, Rachel Lowe, stated: “As climate change continues to alter the habitats of disease vectors like sand flies, understanding these shifts can help mitigate the spread of leishmaniasis and other climate-sensitive diseases. Integrating climate data into health surveillance systems can anticipate emerging health threats and support more effective responses.”

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge the following projects: The Lancet Countdown in Europe, IDAlert, CLIMOS, and the European Climate-Health Cluster.

References

Bruno M. Carvalho, Carla Maia, Orin Courtenay, Alba Llabrés-Brustenga, Martín Lotto Batista, Giovenale Moirano, Kim R. van Daalen, Jan C. Semenza, and Rachel Lowe, A climatic suitability indicator to support Leishmania infantum surveillance in Europe: a modelling study, The Lancet Regional Health Europe, volume 43, 100971, 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100971.

Kim R. van Daalen, Cathryn Tonne, Jan C Semenza, et al., The 2024 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action, The Lancet Public Health, volume 9, issue 7, E495 - E522, 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00055-0.